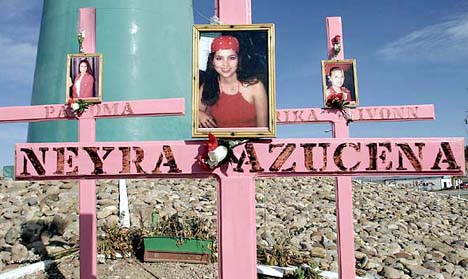

Marisela Escobedo’s life changed forever in August 2008 when her 16-year-old daughter Rubi failed to come home. What was left of Rubi’s body was found months later in a dump -- 39 pieces of charred bone.

Rubi became one more macabre statistic in Ciudad Juarez’s nearly two-decade history of femicide. The murder of young women, often raped and tortured, brought international infamy to the city long before it became the epicenter of the Calderon drug war and took on the added title of murder capital of the world.

But Rubi never became a statistic for her mother. Marisela knew that a former boyfriend, Sergio Barraza, had murdered her daughter. As authorities showed no interest in investigating the case, she began a one-woman crusade across two states to bring the murderer to justice. The Mexican magazine

Proceso recently obtained the file on her case. Marisela’s odyssey tracks a murderer, but it also tracks a system of sexism, corruption, and impunity.

It’s an odyssey that ends with Marisela--the mother--getting her brains blown out on December 16, 2010 as she continued to protest the lack of justice in her daughter’s murder two years earlier.

Trail of Impunity

Marisela Escobedo eventually tracked down Barraza. She had him arrested and brought to trial, and finally saw a chance for the hard-sought justice that could at least allow her to move on with her life.

But in Ciudad Juarez, the term “justice” is a bad joke, especially if you’re a woman. Despite the fact that Barraza confessed at the trial and led authorities to the body, three Chihuahua state judges released him. Marisela watched as the confessed assassin of her daughter left the courtroom absolved of all charges due to “lack of evidence.”

As pressure from women’s and human rights organizations mounted, a new trial was called and Barraza was condemned to 50 years in prison. But by that time, he was long gone and still has not been apprehended, despite Marisela’s success in discovering his whereabouts and providing key information to police and prosecutors.

The story doesn’t end there. Every day, Marisela fought for justice for her daughter and sought out the killer. She received multiple death threats. She responded saying, “If they’re going to kill me, they should do it right in front of the government building so they feel ashamed.”

And they did. Marisela took her demands for justice from the border to the state capital where a hit man approached her in broad daylight, chased her down, then shot her in the head.

A family’s story had come full circle. By all accounts, Rubi’s death came at the hands of an abusive boyfriend. Marisela’s death, however, was caused by an abusive system that sought to protect itself from her determination to expose its injustice. The gunman's identity is unknown, but responsibility clearly lies with members of a state at best incapable of defending women and at worst culpable of complicity in killing them.

Gender Violence and Drug Violence

Ciudad Juarez in recent years has been described as a no-man’s Land, where legal institutions have lost control to the armed force of drug cartels. The femicides show us, though, that the causal chain is really the reverse.

Seventeen years ago, Ciudad Juarez began to register an alarming number of cases of women tortured, murdered, or disappeared. Over the decades, national and international feminist organizations pressed the government for justice. The government in turn formed commissions that changed directors and initials with each new governor. They all shared one distinct feature: never getting anywhere on solving the crimes of gender violence, much less preventing them. Recommendations to the Mexican government piled up alongside the bodies: missions from the United Nations and the Organization of American States provided over 200 recommendations on protecting women’s rights, with fifty for Ciudad Juarez alone.

Marisela’s murder marked a year since the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a ruling calling the Mexican government negligent in the murders of young women. The ruling on the

“Cotton Field” case--named after the lot where the bodies of three women were found on Nov. 21, 2001-- includes a list of measures and reparations, most of which have been rejected or ignored.